For many years I have been fascinated by the contemporary countertenor movement. My interest was spurred by after listening to a broadcast on NPR’s “All Things Considered” about singer David Daniels, who found his true voice after an unsuccessful attempt to become a classical tenor.

For many years I have been fascinated by the contemporary countertenor movement. My interest was spurred by after listening to a broadcast on NPR’s “All Things Considered” about singer David Daniels, who found his true voice after an unsuccessful attempt to become a classical tenor.

My curiosity was further peaked by the movie Farinelli (1993), which was a lascivious adaptation of the life and career of famous 18th century castrato Carlo Broschi.

In order to recreate the vocal timbre and wide tessitura attributed to castrati, the singing voice of Farinelli in the film was Frankensteined together from the combined voices of a female mezzo-soprano and a male tenor, which resulted in a somewhat effective, but likely inaccurate approximation of the Baroque castrato voice.

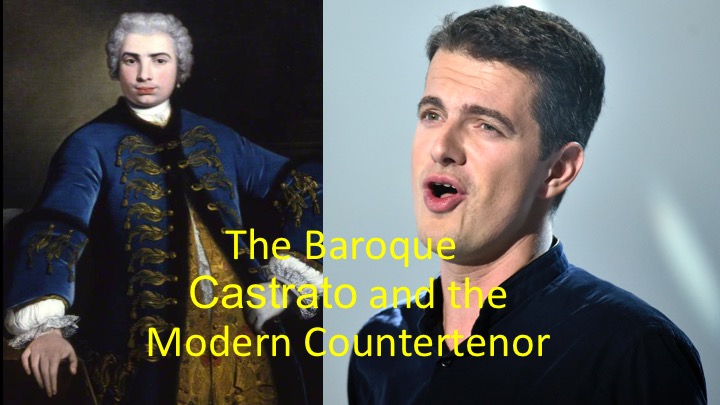

Castration of young boys with gifted high voices began in Italy in the mid-16th century. Select individuals were emasculated before reaching puberty, resulting in the retention of the pre-pubescent larynx (small vocal cords), but mature development of the chest cavity and lung capacity of adulthood. Castrati or “musico” were sought-after commodities among the aristocracy and the Catholic church in the 17th century. In religious contexts castrati sang the high harmonies because women were prohibited from singing in church.

At the height of the castrati craze between 1720 and 1730 an estimated 4000-plus boys were castrated annually in the service of the art. It became a common practice in 18th-century Baroque opera to cast castrati in women’s theatrical roles, and many renowned composers from that era, including Monteverdi and Handel, wrote specifically for the castrato voice. A 19th-century shift in preferences for featuring female sopranos in operatic roles relegated castrati to strictly religious contexts, which continued until the end of the century. The last bastion of the castrati ironically seems to be at the Vatican Sistine Chapel.

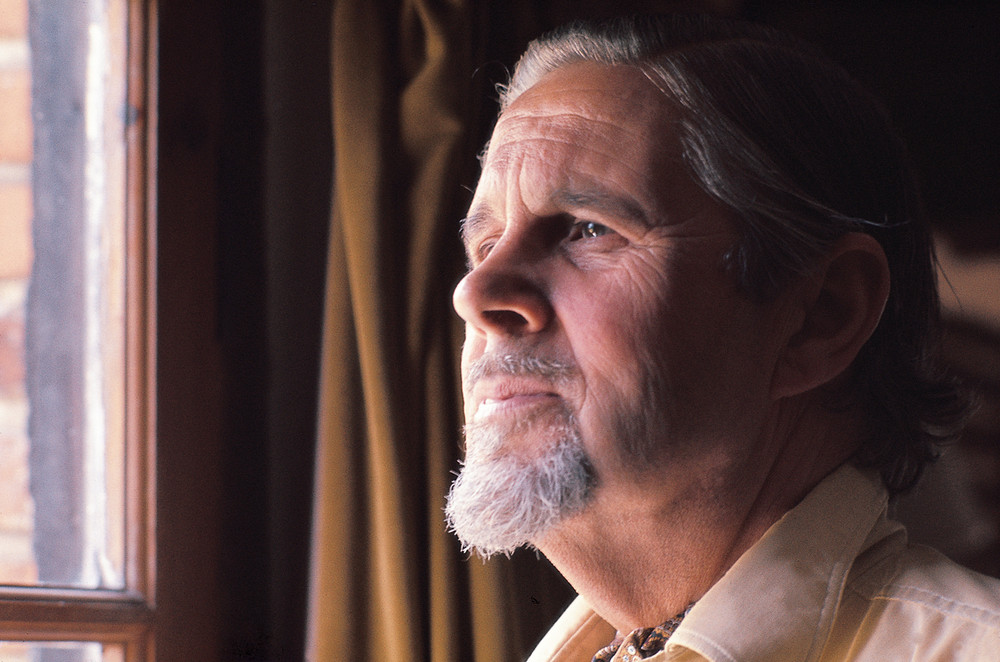

It is important to note that, aside from descriptive accounts, there is no clear example of what a castrato actually sounded like. The “last” known castrato was Allessandro Moreschi (1858-1922), who sang in the Vatican Sistine Chapel Choir from c. 1883 until his retirement in 1913. In 1902 and 1904 he recorded a number of selections on wax cylinder in Rome for the English Gramophone Company, which are available on CD.

The low-fidelity of the recordings, the scratchiness of the wax-cylinder format, and poor quality of the performance in terms of breath support and intonation makes it very difficult to get an accurate picture of his vocal acuity. Although this 2017 digitally-enhanced “scratchless” version of Alessandro singing “Ave Maria” in 1902 presents a much better idea of how the natural castrato voice would have sounded, the musicality of the performance is severely lacking.

In my mind’s ear, the closest affected representation of the castrato voice to date is the “Diva Dance” segments from the 1997 film, The Fifth Element. Although it was made only four years after Farinelli, technological innovations created a more believable “castrato” voice for the androgynous alien diva Plavalaguna, portrayed by French actress Maïwenn Le Besco, with an digitally-enhanced auto-tuned voice-over by Albanian soprano Inva Mula.

Despite its electronic artifacts, the power, clarity, and the facility often attributed to virtuosic Baroque castrati does seem to be apparent in Plavalaguna’s scene, which comingles the mad-scene aria “Il dolce suono” from Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor, and the EDM-inspired “Diva Dance,” with its huge vocal range and acrobatic melismatic passages.

The 20th Century Countertenor

The countertenor voice is apparently a mid-to-late 20th century phenomenon. Countertenors often begin as baritones, but then raise shaping their tessituri into the countertenor range through the use of falsetto technique. Beginning in the late 1940s, the twentieth-century countertenor revival was heralded by Englishman Alfred Deller, who reprised selections from the age-old Baroque male soprano repertoire.

His American countertenor contemporary was Russell Oberlin, another pioneer of early music revival, whose career blossomed in the 1950s and 1960s.

Contemporary Countertenors

Beginning with the emergence of American David Daniels in the early 1990s, there has been a steady growth on the number of, and demand for, countertenors.

Some of the other top names in the genre include fellow American Bejun Mehta, German-born Andreas Scholl, and Frenchman Philippe Jaroussky.

Jaroussky “Vedrò con mio diletto” from Il Giustino, Verdi (1724).

Complicating the contemporary countertenor craze is the arrival of the male soprano whose natural vocal range extends into that of the countertenor without the use of falsetto technique. As with some of the musico from earlier centuries this phenomenon occurs as a result of a hormonal abnormality during puberty, rather than by a purposeful means.

One such individual is Michael Maniaci, a classically-trained American opera singer, whose voice did not “break” during puberty and sings in the upper register without falsetto technique.

The Countertenor in Popular Culture

Despite all its art-music connotation, the high-male vocal phenomenon permeated popular culture throughout the 20th century. An early noted example is Western yodeler Tex Owens who penned and recorded the classic tune “Cattle Call” in 1934.

“Cattle Call” continued its popularity into the mid century when it was re-recorded by numerous other country singer including Slim Whitman and Eddy Arnold, for whom it became a signature tune.

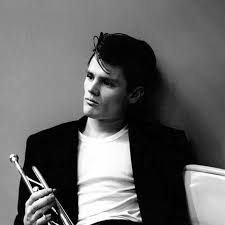

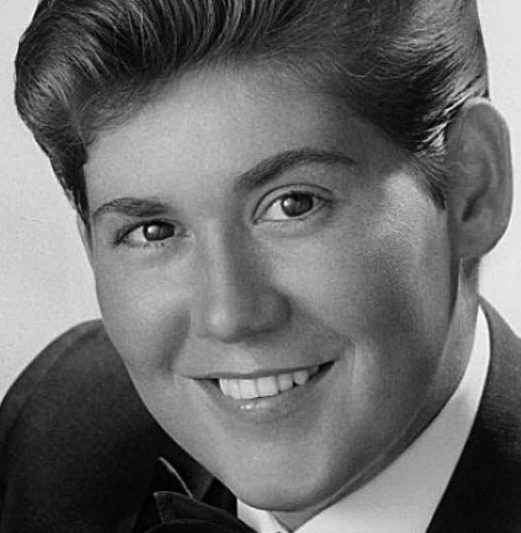

Although not identified as countertenors per se, the high male, almost androgynous, vocal tone became the trademark sounds of artists such as 1950s crooning jazz trumpeter Chet Baker, and teen-age phenom Wayne Newton.

Chet Baker “Everything Happens to Me” (1958)

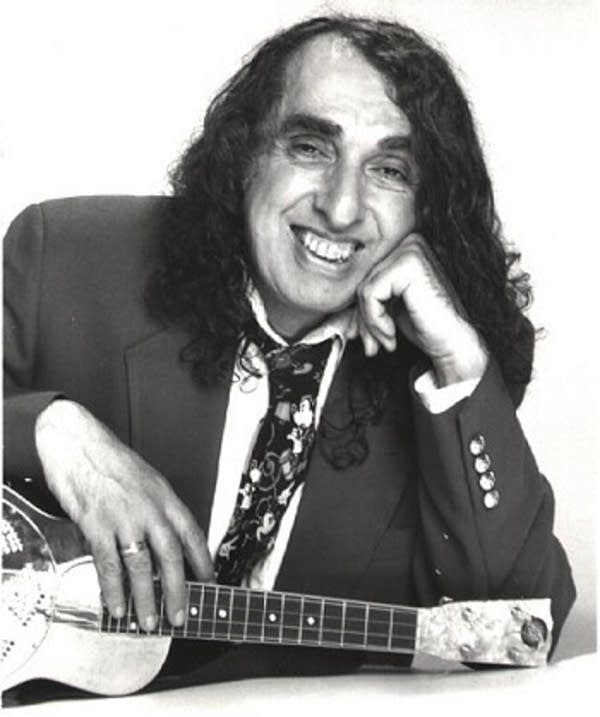

Notable examples of the high male voice in the 1960s included Motown’s Smokey Robinson and English folk falsettist Tiny Tim.

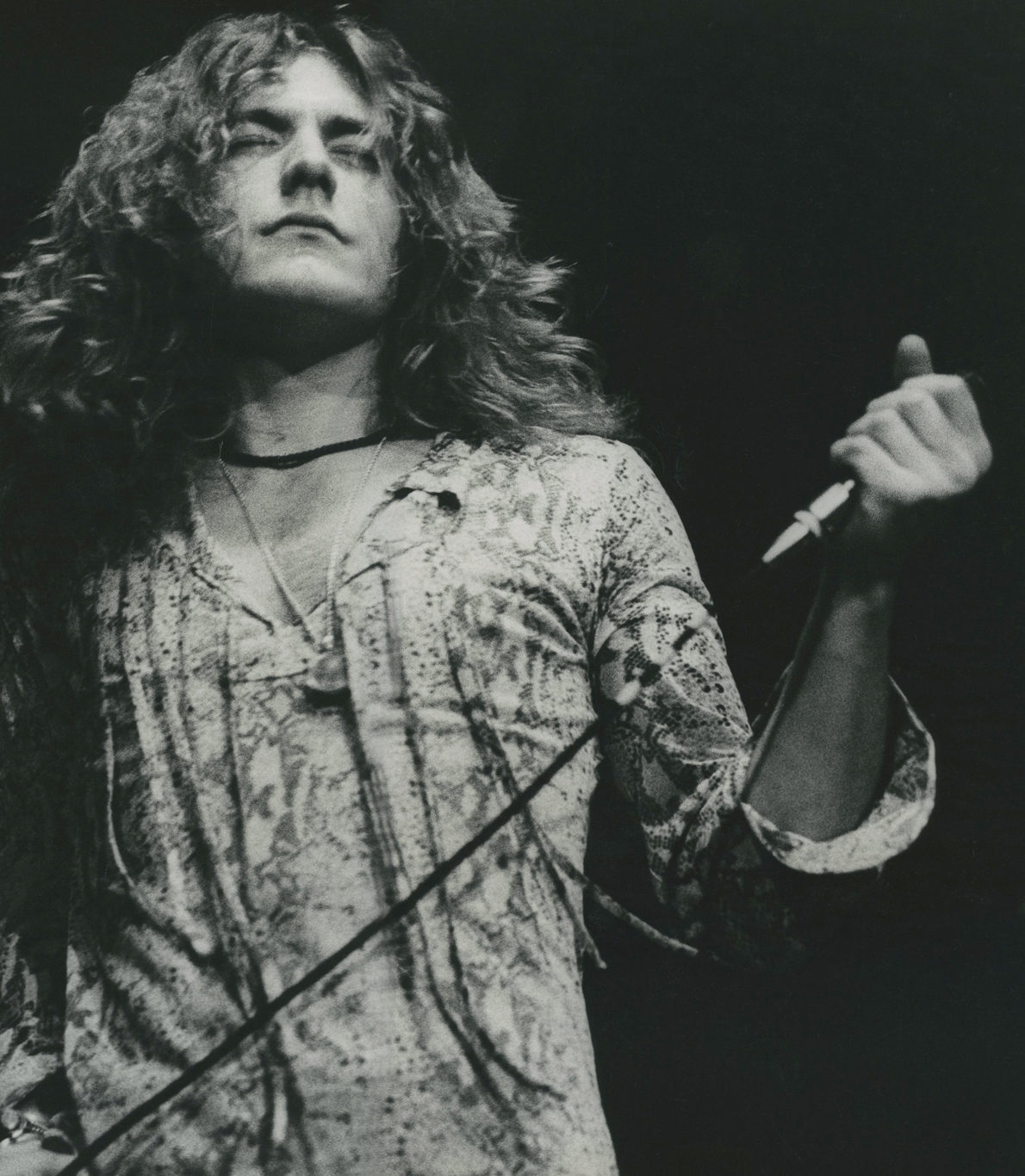

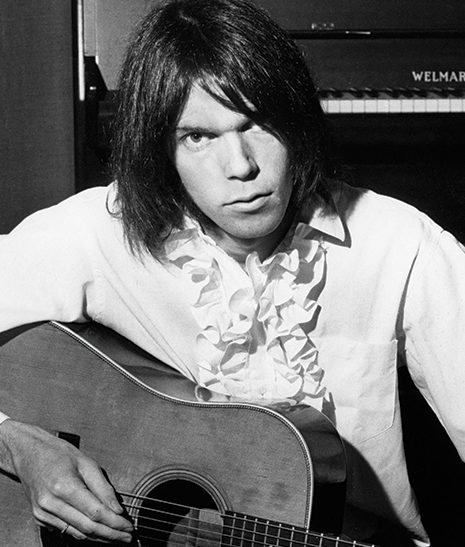

From the late 1960’s and beyond Canadian Neil Young, with his high natural voice, was instrumental in bridging folk and rock mediums, and Led Zeppelin’s Robert Plant was the poster-child for a plethora of “metal” singers to follow.

However, the top rung in the high tenor ladder must be occupied by Freddie Mercury (born Farrokh Bulsara), who shattered the glass ceiling of the classical tradition with his incredible vocal range on Queen’s A Night at the Opera album.

Into the 21st Century

Where the countertenor revival will lead is anyone’s guess. In the rock idiom, Adam Lambert seems to be seated soundly in the vacant throne of Mercury. But, perhaps a glimpse into the future can be gleaned from the musical idiosyncrecies of Latvian-born Vitaliy Vladasovich Grachov, aka “Vitas,” whose five-octave vocal range is well-suited for a wide range of genres, from classical, to folk, and popular music.

If a conclusion is to be drawn from this brief observational study, it would have to revolve around the notion that in this age of digital processing and auto-tuning, that there is still a human fascination with the varied remarkability of the natural human voice, as evidenced by Vitas’ signature “turkey call” vocalaise, which has garnered over twenty-two million YouTube hits.

However in an ever-changing YouTube world, nothing is permanent as expressed by this musical answer to Vitas by Dimash Kudaibergen from Kazakhstan, who raises the bar several notches in his high-altitude cover of Vitas’ “Opera #2.”

Now I’m down for the countertenor battle royale of the future. To be continued…